AUTHOR INTERVIEW with Roy G. Guzmán

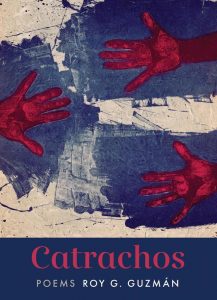

On December 3, 2019, editorial board members of Runestone Vol. 6 had the opportunity to interview poet Roy Guzmán. Roy is a Honduran poet whose first collection, Catrachos, is coming out from Graywolf Press in May 2020.

The interviewers were K McClendon and Kelly Holm.

Roy G. Guzmán was born in Honduras and raised in Miami, FL. They received their MFA in creative writing from the University of Minnesota, where they’re currently pursuing a PhD in Cultural Studies & Comparative Literature. Their work has appeared in Poetry, The Rumpus, Hayden’s Ferry Review, and The Academy of American Poets. After the Pulse nightclub massacre in Orlando, their poem “Restored Mural for Orlando” was turned into a chapbook to raise funds for the victims. In 2017, they were named a Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Fellow. In 2019, Roy was the recipient of a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. Roy’s first collection will come out from Graywolf Press in 2020. Visit Roy’s website.

Kelly Holm is a member of Hamline University’s class of 2021. She is an award-winning student journalist for The Oracle and an English and creative writing double major. Besides Runestone, she’s interned with Sentinel Publications, Elicit Magazine and GenZ Publishing. She hopes to find work as a professional writer.

K McClendon is a junior at Hamline University where they study creative writing. K competes nationally as a spoken word artist. They have been an avid Button Poetry fan for many years and are an intern at the company.

K: You just finished your collection [Catrachos] and it’s coming out. Tell us a little bit about it.

Roy: Absolutely. Thank you. Well the first draft of Catrachos was finished in 2016 and around 2017, a major section in the book was gutted out and that gave me some opportunity to think about, not just reordering the manuscript, but what other poems I could include in it. The second section in the book was supposed to be something along the lines of a lyric essay. It was sort of an homage to my mother and then a lot of the feedback I kept receiving consistently said that that had to be its own book, its own project, so I took that out, and of course since then it’s grown into its own project. I think that the version that people will read is closer to the 2017 version.

Roy: Absolutely. Thank you. Well the first draft of Catrachos was finished in 2016 and around 2017, a major section in the book was gutted out and that gave me some opportunity to think about, not just reordering the manuscript, but what other poems I could include in it. The second section in the book was supposed to be something along the lines of a lyric essay. It was sort of an homage to my mother and then a lot of the feedback I kept receiving consistently said that that had to be its own book, its own project, so I took that out, and of course since then it’s grown into its own project. I think that the version that people will read is closer to the 2017 version.

There’s a lot of different themes I deal with. I deal with not just queerness, I deal with being an immigrant, issues of labor, having grown up in Miami and what that meant as a person of color—a poor person of color. Beyond that I graduated—I went to the University of Chicago for my undergrad—and so Chicago has a mix of cameos here and there, but it’s primarily set in Miami and Honduras where I was born, so I deal with a lot of that. Very personal poems, but also poems that raise this figure of the Queerodactyl, which is sort of like a book within the book. It’s this creature that’s like a hybrid of different things that sort of thinks about, how does one survive when everything seems to be under attack? It incorporates Pulse, a lot of pop culture, drag scenes like the drag ball.

K: Beautiful. That transition from Miami to Chicago, that was probably a whole thing. [Laughter] I love that personification of the Queerodactyl and giving that a form because then it’s easier to talk about it when we know what we’re looking at.

Roy: It’s very visual. Because it’s visual, it’s also very colorful. I think one peer in my graduate program is credited as saying that it feels like a hologram. It feels like so there are so many textures that are happening on different dimensions. And for me that’s important, like how we give language to forms of queerness that perhaps seem to be misrecognized or erased. That’s all there.

Kelly: You wrote “Restored Mural for Orlando” after the shooting in 2016. How do you think poetry functions in times of tragedy such as those?

Roy: I edited the poem slightly. It will be in the book. I had considered not having it in the book because it felt like I wrote that poem in the spirit of honoring the dead, honoring all the victims. As I was thinking about, by the time the Pulse massacre happened, I had already been writing some of the Queerodactyl poems, and so I was already in that space of the club, that space of chosen families and things like that. It was very difficult to write about a tragedy that just occurred. I think a couple days after it happened, that’s when I wrote the poem.

It feels like years and years went by between the tragedy and the poem coming out. There’s something about tragedy and what it does to time and to emotions and whatnot that felt very strange. The poem goes viral a couple days after, and it was one of those situations where, as the poem goes viral, I sort of sat back and not just tried to deal with my own grief, but also the grief of families who lost loved ones there, and the survivors, but also my friends who also had friends there who lost their lives. I used to believe that when it came to grief and when it came to these sorts of profound, national traumas that you had to wait some time to write about them. In some ways I do think that time is important. I think for me, the impetus behind writing that poem was partially because I was very angry in the stages of grief and I got to the point of being very angry that straight white people were being handed a microphone to talk about this tragedy when in fact, that was not the community that been impacted by this. That’s when I felt like I had to say something because some of us in queer, black, brown communities are looking at one another. Like we’re all hurting, we don’t know what to do with this tragedy, we don’t know how to write about it, and yet there is this production and publication of poems written by people who had no attachment to the ways in which the violence there affected people intersectionally.

That is how I felt like I was able to respond to that. I don’t think I would change anything in terms of how I responded or when I responded to the tragedy. Soon after the poem was published, I was asked to serve as a co-editor for an anthology honoring the victims, and I remember coming across some editors and people who said like, ‘I mean, come on, the world has moved on. Why are you still writing about this?’ I mean, there are national bestsellers dealing with the Holocaust, dealing with wars that have happened historically, texts coming out about the Romans, but somehow this is already dated? It made me, of course, reflect on how violences that affect people who are marginalized end up being relegated as ‘you already had your 15 seconds of fame, you already had your mic, step away, it’s time for the cis, heteronarrative to come back and continue its virals.

Kelly: What do you believe about who can tell what story?

Roy: I don’t believe that people cannot and should not have access to stories and to write about those stories, but I do think there are ways to prepare people to write those stories. Historically when we look at the production of literature, straight men have failed at writing women, for instance, men have failed at writing erotica, sexuality, sensuality, and so I think there are so many examples and we could reflect on and say ‘well everybody should be equipped with better handling of these topics’. For instance, when it comes to stories about Central America or being Honduran, traditionally it’s been the white man who gets the money and goes to write about a culture that isn’t his. To me it’s not that I think he shouldn’t be writing about that culture or my culture, it’s a problem of why is it that that’s the only voice that gets funded, why is that the only voice that gets recognition, when in fact, people in the ground, people who are from those geopolitical areas are already speaking for themselves. What are we doing about those voices? What are we doing about translating that work?

K: I was thinking about how you said that people were asking you to move on from it [the Pulse massacre]. As a spoken word artist and somebody who participates in slam a lot, there’s a lot of Black people who write about Blackness and I know how hard and awful it is to be Black in this country. You have a lot of people complaining about that and complaining about the fact that there’s all these Black folks talking about the same thing over and over again, but what I’m thinking about is what you said about that why can’t this be the narrative? Because the cis, straight, white narrative is always the narrative, so why are we pushing back when all these people of color are in the narrative?

Roy: Absolutely. It is a symptom of not just white supremacy, but it’s a symptom of capitalism where if you’re quote-on-quote bored with this narrative, suddenly you want to flip the channel.

K: Right.

Roy: Right. And there are times that we dismiss—especially fundamentally in thinking about American history—dismiss the oppression. It’s like the minute you talk about subjectivity or what it’s like to walk out on the street and get to work, you’re already talking about people who are being affected intersectionally, whether it’s gender or class, so that idea of tiredness is something I often think about. Who is supposed to consume my stories? Traditionally it’s been the people who have money, or it’s been the middle-class, and there’s something to say in which the ways the middle-class in America has in fact created pockets of what they think people should talk about at Thanksgiving. Now we’re having all these questions of how you confront your racist uncle at your Thanksgiving, whereas before it was just like hush, you don’t speak about it, you go and dress the way you want to dress outside of this space but you cannot contaminate this space. It’s a very bourgeois symptom. It’s one symptom the American middle-class started drinking up. And not just white people.

K: I’m assuming you read Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me?

Roy: Yeah.

K: It’s like that. Like the whiteness being able to be end-one.

Roy: Oh yeah, absolutely. The sort of being tired, like tell me a new story, tell me something else. I think so much about, in your question, the foundation of Arabian Nights. Scheherazade, she’s supposed to be telling these stories and she’s telling these stories as a way to survive and if she doesn’t tell a story that’s compelling, she’s going to be killed. So often the people of color, marginalized people have been tasked with this hyper-production of entertainment, whether it’s consumption of Black bodies, consumption of Black entertainment or LGBT entertainment. We continue to see this and it’s hard for us to start thinking about our liberation if we’re constantly having to produce things that will satisfy this mass of people who have the money and the means for me to eat.

K: It kind of goes back to if you grow up Black, your parents will say to you at some point that you have to work twice as hard to be seen as half as good as those white kids. That’s that over-production. To lighten it for a second [Laughter], what media outside of literature inspires you?

Roy: Lots of media! I love music. Music is a thing I can’t live without every day. I need it. I play a lot of Spanish ballads, ballads that came out of Mexico for instance, or Argentina. I also play a lot of disco. I love disco and I love your big pipes from the 80s, like Tina Turner. I don’t remember when, but Patti LaBelle came to Magic City and I was asked to go onstage and sing with her and she was like ‘you can sing!’ [Laughter] It was a big honor, and I think about that moment of how music continues to be an inspiration to me. All genres. I also love movies. My partner, he loves TV series. I can do them, but it’s a slow process for me. I want to either watch all of them at once or I don’t want to watch at all. I’ve been finishing The Crown, I just finished watching Big Little Lies. There’s something about watching white people, especially rich white people, get after each other. [Laughter] I went to see Hustlers recently. It’s reparations! It’s exactly what that movie was about. I’ve been reading a shit-ton of Foucault for my own work and for this term paper that I’m looking at, and within that, just a lot of poetry. Poetry is a thing in my everyday life.

K: Do you have a backpack book? What poets would you keep in your backpack?

Roy: Oh my Lord….Patricia Smith is just incredible. Today I was talking to my mom and I was trying to translate the concept of a book blurb. [Roy passes out an ARC of their forthcoming book Catrachos and the class gets excited] One of the blurbers is Heid Erdrich. I love, love her work! The blurb came in today and I went goo-goo-gaga over that! We just have incredible poets here like Sun Yung Shin, Bao Phi, of course your canon would be illegitimate if it didn’t have Danez [Smith]. A lot of Native poets are doing incredible work. Layli Long Soldier, Natalie Diaz…just breathtaking. Along with that, I’ve seen a lot of work by writers from Asian diasporas and that’s been really helpful. Not just writers like Sun Yung Shin, but I’m thinking of other Korean writers like Su Hwang, Chinese writers to Japanese writers. Yeah East Asia has been a huge influence on me, so I’d keep a lot of them in my backpack. [Laughter] And of course, Latinx writers. Right now, Latinx writers are doing some incredible work. I’m always so jealous. It’s like, how did this poem come to you? How did you write this? How many drafts did you have? We both have this shared experience and somehow you thought about writing it. Like damn! Erika Sánchez is an incredible writer… Eduardo Corral, who is also providing a blurb… Patricia Smith is providing a blurb… Kaveh Akbar writes really just beautiful work that’s heartbreaking.

Kelly: What affect has academia had on your writing? What would you say to those who claim it’s elitist?

Roy: You know, those are questions I ask myself every day. [Laughter] I have to ask those questions because if I don’t, then I lose sight of what my intentions are. In my academic work, I do a lot of theorizing of Central America, but I also go into issues of migrant and gendered labor. I think about political economy and decolonization. I find that poetry actually makes me a better writer than someone who has just been trained in academic writing. You can smell academic writing from so far away. It’s coming at you in this monotonous, robotic, formulaic voice. Something I think about in my writing is how do I allow the reader to get a glimpse or grasp of what I’m working on or what I’m about to argue in my dissertation, but also, how do I invert those things? Poetry has made me a better reader. Not just poetry but also the MFA experience. CNF has been incredibly helpful in thinking about how one continues to bring attention to the subject, to myself, writing about these materials and these experiences when in fact traditionally, the I/me has been divorced from the writing. CNF has also been great in thinking about form and style. When I think about keeping the reader entertained, I think about fiction. All of these different genres enter into my sphere of academia by forcing me to read literature and really think through the lens of something I never would have done through my own volition. It’s put me in spaces of discomfort and academia reminds me of what I’m there to do. As a person of color, there are pioneers and major influencers in my work that have come out of academia.

I know that it’s been very difficult to translate to my family what my work is and why I do it. My parents had aspirations of me becoming a lawyer. I worked in a law firm for a couple of years and I just didn’t like that pace. I didn’t like the mentality. I did a lot of math in undergrad and I thought I was going to be a chemist. With all of these terms that have particular currencies that are more legible for my family, I’ve had to invert them. As a poet I’ve had to explain to my parents that I’m still dealing in rigorous research, I’m still dealing in rigorous writing and intertextuality. I’m still invested in history and economics. For me, that pedigree of elitism isn’t something that necessarily applies to me because as an immigrant and poor person, the fact that I even graduated from high school was a miracle. The fact that I’ve even gotten this far. I’m now stacking, not degrees, but ways of talking about me and ways of talking about my family’s experiences.

K: How do you manage self-care, especially with this background that you have, and you that now find yourself in a lot of systemic white spaces?

Roy: Self-care for me primarily comes in the form of food! I’m always open to trying out new cuisines. Beyond that, I love video games! I love interacting with video games. They help me theorize beyond what I’m already doing. They also help me think about things in my imagination. I get ideas for short stories from video games. Self-care to me is also friendship. Constantly having people who help anchor me is a form of self-care. These are people who will bring me back from the static.

Student: Can I ask what video games you like?

Roy: So, I just finished the very first part of Final Fantasy 14, the PC version. Beyond that, I’ve engaged a lot with Overwatch, The Division, The Division 2, Horizon Zero Dawn, Pokémon, Fallout, Outer Worlds. I know I’m forgetting some but those are the primary ones.

Kelly: How do you balance your personal ethics with the need to make money and the need to lives up to others’ expectations?

Roy: I have an unofficial committee of no, and these are people who advise me on professional, personal, financial matters. What things I should be doing for personal growth, for academic growth, and which things I should just let go of. My advisors are definitely part of my committee of no. I find that capitalism just makes everyone gross! We’re all gross and complicit! [Laugher] This question of ethics becomes very slippery often when you need to get paid. Because capitalism monetizes and taxes everything, I believe that poets should be paid, and that’s something that other poets say is wrong. They ask, ‘how can you dismantle the system if you are tying creative writing with money?’ For me I’m thinking of how fiction writers publish their novels, or look at the memoir. They’re selling their books. Why is it that for me to go somewhere and read for 10-15 minutes isn’t already using labor, and me having to get paid for that labor? Dismantling capitalism is in some ways a paradox if I have the money and power to dismantle it. Often times the people saying poets shouldn’t get paid are people who have money. They’re the people who are just like, ‘Oh one day I woke up and I decided I just wanted to get an MFA’ [Laughter] and it’s like, really? An MFA for me was a very intentional journey. It wasn’t just me sitting around and thinking something about Flannery O’Connor. [Laughter] Me really thinking about craft and wanting to learn from someone, wanting to be mentored, I wanted that. I get this idea of ethics and this involves that. I also try to mentor people. I think about women and how they get exploited in the literary world in many different ways…sexually, financially, with their time. I think about mentorship as an ethical way to dismantle the system by allowing people to understand that there are other ways to create intimacy and navigating rejection, navigating self-doubt.

K: How do you balance being a poet and a student? If poetry is your student life—is there poetry outside of that too? Do you feel like that’s the same? How do you navigate that?

Roy: That’s a very good question. I don’t really know how to balance that well. Mind you, I’m also the kind of person who is already going to ask, ‘Well what is balance? How is balance a bourgeois thing?’ The navigation part is definitely clumsily. I unfortunately end up saying yes to many more things than I should be saying yes to. I also find that my poetic productivity has sort of diminished because I’m writing more prose. I’m constantly having to write more prose, but I’m still thinking about poetic language. My department doesn’t really know what to do with artists, so it’s not just me. There’s a professional musician and there’s a fiction writer, and in the new class, there are two poets and a musician, who are professionals in their field. That’s an ongoing conversation. How do we in the department—if we want to diversify the department, not only in terms of accepting people of color, queer people of color, etc. but also accepting artists—how is it enabling artists to continue that practice? How is it actually getting in the way of creative output? For me, it’s kind of in the way of a lot of my creative output. I get solicited and often I have to say no. I know that I have a lot of files in my computer and that’s just work that I need to revisit. It’s hard to do that. In fact two days ago I was in the shower and I ended up having to record a poem on my phone because I knew that if I exited that shower and in the process of getting dressed, setting up a good work space, I would have either lost interest in that poem or my mind would’ve shifted to something else. I’m trying to do things like that, finding other ways to honor the creative process. One thing I purchased recently was a basic iPad because I want to be able to work with my fingers if I need to draw something as a way to think about an image that I can revisit, and with my laptop, I wouldn’t be able to do that.

Kelly: How do you see digital literary communities and local literary communities as differing in what they offer and the types of spaces they create?

Roy: That’s an excellent question. I have benefited a lot from having a digital presence and making lots of connections digitally. I started out with a WordPress blog. I was just posting things and reading other people’s writings, and I remember that there was a point for a tangible demand for my work from my blogger peers. I remember thinking ‘How can I give them something without necessarily giving out these larger projects?’ I started working intentionally on haiku. If I could give them a little taste of my work through haiku, not only could my output be more consistent, but I could also learn something about poetry through haiku. That’s how I found an audience. I started sharing some of these haikus on Facebook and a friend said that if I shared them on Twitter, people would actually like them. When Twitter first came out, I wasn’t very interested in it, but I started an account and started posting my haikus. In one of my interviews I mentioned that I opened up my Twitter account in 2012. 2012 Twitter was so different. People shared so many quotes of texts, quotes with images, a lot of inspirational work. I was able to find communities there. I was exposed to tons of journals there. Editors from journals would read my work and contact me. It grew to a network of exchanges with so many different people. Parents, sex workers, trans people…..cooks. [Laughter]. Politicians. And somehow, we find this common language. I have been exposed to all of these writers across the world and they’ve all exposed me to different voices. You know, it’s a reminder that the US creates a very narcissistic, very egocentric notion of itself. That quickly falls apart the minute you start to interact with people outside the US.

I’m so grateful in terms of this community here in the Twin Cities. I applied for my MFA at the U because I wanted to work with Ray Gonzalez. He’s a writer from El Paso and he’s lived here so many years. I was actually teaching his work to Latinx students in Miami and little did I know that years later I would work under his wing. The literary communities at large have been extremely supportive of me through resources, knowledges, through money, through gigs. At least one person here is blurbing my book. When it came to readers for drafts of my book, you’ll see that I have so many people in my acknowledgements page! I’m thanking the cooks at Popeye’s! [Laughter] There were times when I was so lonely here and people would just say ‘Come here and work on your stuff. No one’s going to kick you out.’ Some of the teachers and alumni here at Hamline have been incredibly supportive. Augsburg, Mankato, as well. One of the things I thought about when I was applying here was what if I could get published by a local press and that is what’s happening! Graywolf has such a massive influence in the literary world. I’m really grateful for that. When it came to revising the book, editing the book, I could actually meet with my editor to talk about logistics, or a cover. The ARCs came in when I was in the office talking about touring and publicity and marketing, and I was just bawling! Like holy crap, this is finally real! It’s rare to have that opportunity elsewhere. There’s less of that person-to-person contact. Back in the day, you used to go to New York to become a writer and now Austin has an incredible literary scene, Arizona, Michigan, Wisconsin, here. I love these non-New York City narratives.

Kelly: What roles have grants, fellowships, scholarships done for you?

Roy: I cannot stress enough the importance of grants. Minnesota has money for artists; it’s incredible. I think being here in Minnesota is where I was taught that not only should you get paid for your work, but also that you can carve out time for your work. You can get a Minnesota State Arts Board grant which I think is 10K max. With that, we’re talking about two, three, fourth months—for some people it’s more than that—where you can just be off school or off work and just focus on your own work. What really provided me the model is a fully funded MFA. That allowed me to accept that it is ok to take time off work or other responsibilities to do something creative. Fully funded MFAs are very rare to come about. They’re incredibly competitive, and sometimes you have no idea why you got in over someone else. For me, again, that was important. After that, the Minnesota State Arts board grant. And then beyond that, I’ve also been financially supported by the Poetry Foundation in Chicago, the Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg fellowship. I don’t know if you know this, but every year they choose five poets, and every poet is given 25K. And yeah, I received one of those…that’s a lot of money! [Laughter] I feel like when you get that as a poet, suddenly you realize you’re almost resurrected to do more and to invest more in yourself, and also other people. This year I also got a National Endowment for the Arts grant. Those are all ways in which I have been supported by foundations, by people, by editors. What I was doing before I pursued my MA, was agitating. I have a Masters in Comparative Literature and I was teaching in Florida. Community colleges, primarily. That was not only my main source of income but teaching and being in those spaces gave me food, creative food, to think about ways to get money. By assigning people’s books, I was able to participate in supporting someone’s career and sustainability. Unfortunately, I think as an undergrad, I came out of school with a tremendous amount of student loans, even though it was fully funded. When you come from a dirt-poor class, you need to take out a loan. You going to school means even less income for the household. You have to be able to replace it in some way, and that’s why I took out a lot of student loans to help my parents, to help my family abroad.

Even in the MFA program, something you have to be very careful about is developing this mentality that if only you know about this opportunity, you’re the only one who can get that. Your chances of getting that are higher than if you share that opportunity with your colleagues. I never came with that mindset to the MFA, and yet I encountered that. Fellowships, grants, are the idea of agents. Who or what can put you closer to this agent? What can allow you to go to a book festival where you can be exposed to other professional writers? How do you create conversations and relationships that go just beyond an email? Any of those opportunities that you have, or if other people mentor and promote those opportunities, those are also ways in which that experience in the future is all building up. I had to do a lot of free work. I still do a lot of free work, but now I’m much more selective about what free work I do. When I first started writing, I was just grateful that at least I’m here! Those models, unfortunately, are prevalent in the arts. And how you get access to these types of opportunities is important. Entropy releases a list every few months of journals, competitions, etc.

Kelly: You’re upcoming book, Catrachos, is named after the solidarity and resilience of the people of Honduras. Can you say a little bit more about what that translates to and how those themes are reflected?

Roy: Let me just read this out loud. I’ve been thinking about reading this out loud at a reading. This is going to be the first time! The epigraph historicizes where the title comes from. In the mid-1800s, William Walker—an American filibuster—attempted to take over Central America and reimagined a region as slave states under United States’ rule. At first, he tried to build a colony in Mexico. After successfully taking advantage of civil unrest in Nicaragua, Walker became president of the country in 1856. With United States President Franklin Pierce’s endorsement, he ruled for a year. During his reign, Walker went to war with Costa Rica and plagued the country with cholera. He was eventually defeated by Honduran General Florencio Xatruch and his troops, which included Salvadoran soldiers. Walker was charged and executed in 1860. Because Xatruch’s name was difficult to pronounce, as Nicaraguans welcomed the general and the soldiers, they yelled, ‘¡Aquí vienen los xatruches!’ From Xatruch’s name, Salvadorians became known as Salvatruchos, and Hondurans as Catrachos.

I wanted to reveal that at some point in the book, because we’re dealing with American imperialism. The entire book is about American imperialism, imperialism producing forms of migration, American imperialism producing forms of gender, forms of poverty, forms of humanity. And so, that ends up being the impetus behind the book. Catracho is like a term of endearment. Catrachos has an anti-imperialistic stance.

[Students request to hear one of Roy’s Queerodactyl poems]

This one is very much inspired by Patricia Smith in that ability of how does one find one’s own music? How does one remember one’s own music? As corny as that sounds, I constantly come back to the Miles Davis quote that “it takes years to sound like yourself.” I feel the same way about this.