REVIEW:

REVIEW:

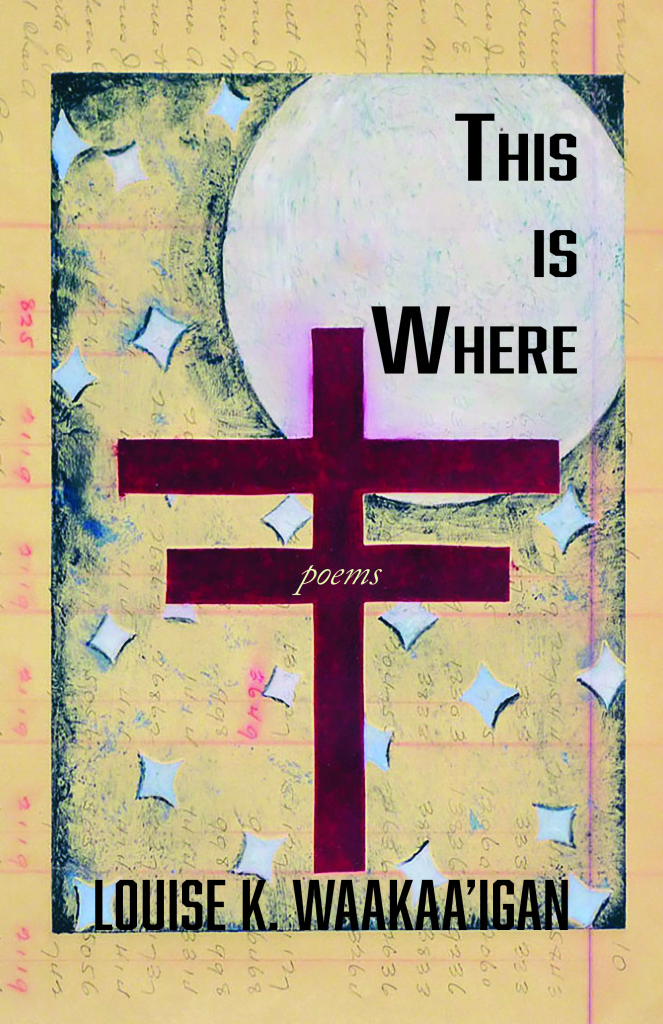

This is Where by Louise Waakaa’igan

Runestone, volume 7

REVIEW:

This is Where

by Louise Waakaa’igan

Runestone, volume 7

Reviewed by Emily Poupart

—

Louise Waakaa’igan, Anishinaabekwe poet and former student of the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop, released her debut poetry collection, This is Where, in the spring of this year. As Waakaa’igan writes in her preface, “It has only been, in part, through my incarceration that I have been able to sit with the experiences of my life and put them to words, not just for my writing, but for my understanding and healing.” In This is Where, Waakaa’igan openly describes her wounds and healing process throughout her incarceration, relationships and childhood in a nostalgic ache and with raw honesty, bringing us with her through each stage of her own realization. We begin with “Within,” as Waakaa’igan reflects on her brutal reality in the winter of prison:

I am a woman gray

within shadows

losing my sense of normalcy

through the monotony that freezes my

already cold spine –

my hands never warm.

Am I not created for more?

Waakaa’igan’s writing doesn’t shy away from describing her own hurt and dark thoughts as she faces past relationships. Struggling with guilt and hopelessness, Waakaa’igan spells out each emotion and turbulent phase of life, including her upbringing in vivid detail as she longs for home:

I’m from Six Mile.

49n up the driveway, sitting on green

boxes watching cars.

Sometimes their doors didn’t match…

I’m from a single-parent household.

Michael Jackson cassette tapes,

Purple Rain posters and latch-key kids.

Title V programs, commods on pantry shelves,

cucumbers from Grandpa Jake’s garden

and a mean ol’ dog name Turkey.

The details of Waakaa’igan’s life are familiar to native readers. It’s common for native communities to be reliant on commodities for food, on Title V for housing, to drive around half-broken down cars or only have the guardianship of a single parent. I felt a connection to these poems because my upbringing mirrored Waakaa’igan’s, I have felt the same disconnect and longing from home, and the same strained relationship to my family and heritage. Sharing these struggles and emotions is a step in the process of healing from and understanding one’s past, and hearing that people have gone through similar struggles may be uplifting to other Indigenous readers. For non-Indigenous readers, this collection can serve as a window into the struggles of Indigenous women, of cycles of violence and abuse that stem from generational trauma and the frustration we feel as these issues and the destruction of the earth go overlooked.

In several poems, Waakaa’igan writes about her father, a man she barely knew, but whose abandonment left her wounded, revisiting the past and repeating his mistakes. We see the poet’s honesty here, in how she describes mirroring her father, in her appearance and in her actions when she leaves the people she loves:

I’m left handed. Was he?

My hair curls. His?

I give up. Why did he?

Then

I knew.

I was the daughter of a man

I did not know, but hated.

I walked away. His initial lesson.

Waakaa’igan’s writing has a way of taking us with her through her journey, sharing lonely, painful moments in “Within”, “Facility Bred”, and “Still”: “I am a foreigner / in my own land, a ghostless shadow begging / to be remembered for more / than solitude.” “I’ve become / an empty shell case in an abandoned room. / Rigidly lonesome / far from lonely highways / I have travelled before. I recognize / this pattern.” “Soul — wounded, / I search for more / than my existence as a fatherless child.” Waakaa’igan draws us into these spaces, into these experiences, urging us to understand them. We see Waakaa’igan as she sees herself: wounded, lonesome, an Anishinaabekwe longing for home.

Waakaa’igan’s collection serves as a memoir, her language contemplative and drawing on memories of people and places unknown to the reader, but familiar to herself, in “Her, Gauwiin” and “Six Mile.” “I will forget / certain things about you, / the surprise of your first kiss, / the elementary proposal in the library.” “Home is/County Road CC, / socks missing, keys hiding, tea cups breaking, / the doorknob falling off, again. / — a cluttered mess with plush carpeting.” We are left to wonder what this author’s life was, as a child, and where growing up and the hardships blurred together. In her preface, Waakaa’igan states “I do not believe I am at the end of this road of discovery. Yet, I have begun.” This is Where is not a complete cycle of recovery and forgiveness. It is an acknowledgement of guilt, the beginning of self-acceptance, and the longing for home, for freedom. This is Where ends with “Six Mile”, a reflection of where home is; for Waakaa’igan, it is the Odaawaa Zaaga’iganiing (Lac Courte Oreilles) Reservation in Wisconsin. “Home / where I long to be. / Miles away, under the same brave moon— / my home … the shelter / I abandoned too soon.”

In This is Where, Waakaa’igan shares her journey of grief, guilt, and healing during her sixteen-year incarceration. Each poem is a meditation on her past, present, and future– on broken relationships, the cold reality of prison, and the idea of what comes afterwards. Waakaa’igan makes a powerful and emotional debut, drawing from her background, Indigenous struggles, and the process of forgiveness and healing.

EMILY POUPART

Hamline University

Emily Poupart is a Hamline senior from Lac du Flambeau, Wisconsin. She hopes to go into publishing after she graduates, and enjoys plants, reading, and being indoors.