REVIEW:

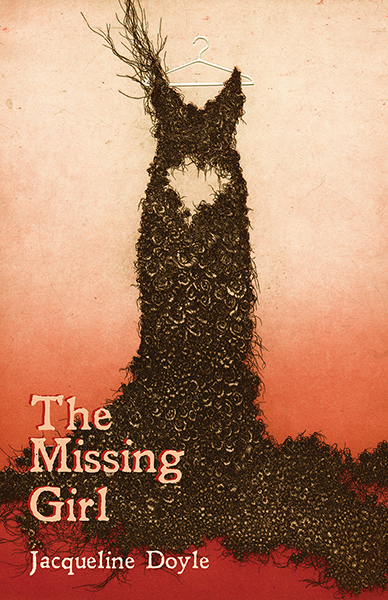

The Missing Girl, by Jacqueline Doyle

Runestone, Volume 5

REVIEW:

The Missing Girl, by Jacqueline Doyle

Runestone, Volume 5

Review by Abigail Morton

Jacqueline Doyle’s debut chapbook The Missing Girl—winner of the Black River Chapbook Competition—features eight flash fiction stories. Each story is an eloquent yet grotesque fictionalization of what is sadly the reality for many girls and women today, centering around rape, violence, and murder. Whether depicting a predator choosing a victim as in the first and title story “The Missing Girl” or the tragic fate of a childhood playmate as in “Nola,” Doyle has written a chilling and compelling blend of social commentary and realistic horror in this prose collection.

Point of view is a powerful tool Doyle wields with expertise throughout these stories in multiple ways. She uses not just first-person point of view but second-person “you,” as well, and does so quite effectively. The use of second person puts the reader not only in the shoes of female victims, but more disturbingly, into the body and mind of the male perpetrator as in “The Missing Girl.” As Elizabeth DiPietro says in her review for Rowan University’s publication Glassworks, “…the reader becomes the killer…In this way, the story is far more effective than it would be in first or third person because there is no narrative distance between audience and narrator. There is no space to get comfortable in Doyle’s world.” Indeed, reading the first story is incredibly uncomfortable, and yet, the reader can’t help but keep going.

Even using traditional first person, Doyle forces readers to get up close and personal with the human embodiment of evil by using conversational language and thoughts that seem rational to many in society’s victim-blaming culture. That is, rational until she puts them in the minds of rapists and murderers: “She swallowed that cherry brandy like it was soda pop…You couldn’t call that girl a victim, not in my book…Sure, she’s only twelve years old…” (18). The familiarity of this train of thought is terrifying, and Doyle knows it and uses it against the reader.

Doyle’s command of form is just as ingenious and varying as point of view. While she uses traditional narrative structure in many of the stories, she mixes it up in others, especially to convey the panic and confusion a victim can feel either leading up to an attack, as in “Hula,” or after an event—or rather, events—such as in “Something Like That.” In these two stories, there are no paragraph breaks; sentences run-on and ideas run together. “…I guess nothing really happened, at least not compared to high school, when I thought I was in love, at least he said he loved me, and then two of his friends showed up when we were making out in the back seat of his car, and they did things to me, and all three of them laughed and called me a slut” (9). Readers are forced to keep reading until they feel just as breathless, confused, and panicked—overwhelmed—as the women in these stories. Just as with point of view, Doyle manipulates the structural elements of prose to put the reader into the content and make them experience what the characters feel.

While these stories are about rape and murder, never once is an actual act of violence portrayed. Neither are the terms rape or murder used in a single story. Rather, Doyle builds tension with clues in all the right places to imply that something horrible is about to happen or already has happened. Again, Doyle knows the familiarity society has with such horrible acts against girls and women, and she uses that against the reader to both horrify them and draw them further in to the collection. This, as DiPietro recognizes, is what makes this collection and Doyle stand out, for “she relies on our societal knowledge to fill in the blanks…and through them reminds us that for women nothing and nowhere is safe.”

Discomforting, disturbing, chilling, haunting, and incredibly familiar in a way that horrifies the reader yet makes them unable to stop. This is Jacqueline Doyle’s award-winning The Missing Girl. In 30 brief pages, Doyle does not just tell eight stories. She makes the reader actively part of the horror, whether as a victim, a perpetrator, or a witness. Her writing dances the line between nightmare and reality in a society where violence against women truly hides around every corner. “You just never know” (3).

ABIGAIL MORTON

Hamline University

Abigail Morton is a senior at Hamline University majoring in English with a creative writing concentration and minoring in women’s studies. She enjoys reading works by Stephen King and hopes to have her own horror novels published in the future, with multiple pieces of such fiction currently in the works.