5 Ways to Survive (And WRITE!) in Our Political Climate with a Sense of Humor, By Alex McCormick

As we all know, the last year has been a trying time for Americans who care about their own future well-being, and it can be hard to feel safe in a country where the fan-favorite former host of Celebrity Apprentice’s main political strategy, is to fire those around...

Is Sexualizing A Character So Bad? By Maya Wesman

Writers often hear about how sexualizing a character reduces them to nothing, and that no one will take them seriously. Many argue that a character can’t be both empowering for the reader, and sexual. I reject that notion. I challenge that idea. Let’s take a character...

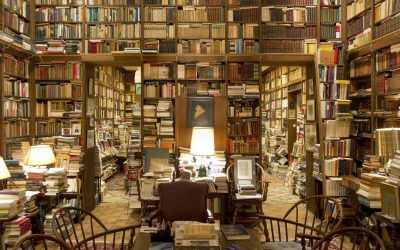

If You’re Not Writing You Should Be Reading, By Meghan O’Brien

We’ve all been there: sitting with a notebook in hand, ready to write the next big piece, but nothing comes. Not a single word. You might think it’s a case of writer’s block you have to push through, and you’re right. You absolutely should push through, but you should...

Recommendations From The Crypt, by Corva Leon

It’s October, and Halloween is slowly pushing its cart of tombstones, candy, and rattling bones up the street, so what’s better than filling your life for a month of spooky things? For people like me October is not just a time to celebrate Halloween, it’s also a time...

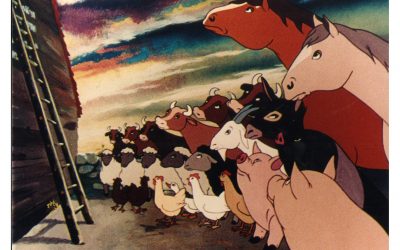

Modern Myths: Rewriting The Old Into The New, by Anna Krenz

As popular culture expands and changes, we as a society are finding new ways to share and tell stories. Old stories come and go, but there are some concepts that just never quite go away. Myths have stayed around for decades, centuries even. These stories tend to get...

Writers & Roleplayers: Lessons in Story-Crafting can be the Real Loot in Tabletop RPGs, By Grant Brengman

If you’ve spent any amount of time with the right kinds of nerds, chances are you’re no stranger to games like Dungeons & Dragons and Pathfinder. But while these games are most commonly associated with various dice-rolling shenanigans, the players are actually...

Into the Sun, By Deni Ellis Béchard, Reviewed By Connor Rystedt

Into the Sun Deni Ellis Béchard Milkweed Editions September 2016 ISBN: 978-1-57131-114-6 464 pages Reviewed by CONNOR RYSTEDT Deni Ellis Béchard's newest novel with Milkweed Editions, Into the Sun, sees the majority of its action take place in Kabul—the capital of...

How Not to Procrastinate, From a Chronic Procrastinator, by Debbie Johnson-Hill

A show of hands if you have procrastinated in the last month, the last week, TODAY. To some, procrastination is a familiar companion; to others, it is a dreaded drain on their time and productivity. So, if we know what it is, why do we continue to do it? The...

Spoken Word Recommendations For Your Zodiac Sign, By Blythe Baird

ARIES When the boy with the blue mohawk swallows your heart and opens his wrists, hide the knives, bleach the bathtub, pour out the vodka. Every time. - “Unsolicited Advice to Adolescent Girls with Crooked Teeth and Pink Hair,” by Jeanann Verlee. TAURUS I say, I am...

So, You Want To Be A Fiction Writer: Tips From The Best, by Caitlin O’Brien

Have you ever finished reading a great piece of fiction...one that left you breathless, excited, yearning for more? Maybe you’ve even dreamt about writing your own work of fiction that does just that. If you are just beginning your journey into the writing world,...

Magic Binds, by Ilona Andrews, Reviewed by Rachel Bakke

Magic Binds Ilona Andrews Ace Books September 2016 ISBN: 978-0425270691 336 pages Reviewed by RACHEL BAKKE In 2007, Ilona Andrews introduced readers to Kate Daniels, who stomped through Post Shift Atlanta with a sword in her hand and vengeance in her heart, ready...

The Boiling Point: Critical Contemporary Albums on Blackness, by McKinley Johnson

Race is a subject that bring with it many negative emotions, making it hard to talk about, and some people avoid it all together. But some musical artists think of this as an entry point to the conversation, jump past or sometimes right into the middle of those...