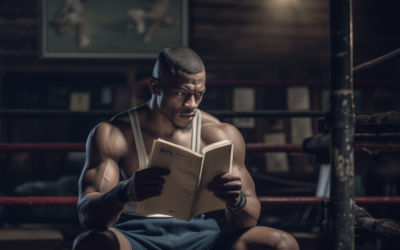

An Athlete’s Guide to Creative Writing

Being a creative writing major, one could expect me to be writing five days a week. Instead, I get punched in the head five days a week. I’ve been training Muay Thai for the past year and a half and recently had my first fight. There’s a level of guilt I hold for not...

American Wallpaper: Misrepresentations Through the Decades

Being an adopted Korean in the late 1990s and early 2000s in the peak of boy bands and sparkly pop princesses was, for a lack of a better word, hard. Sometimes, I would cheer for the white brunette just to feel relevant. While all my friends drooled over Justin...

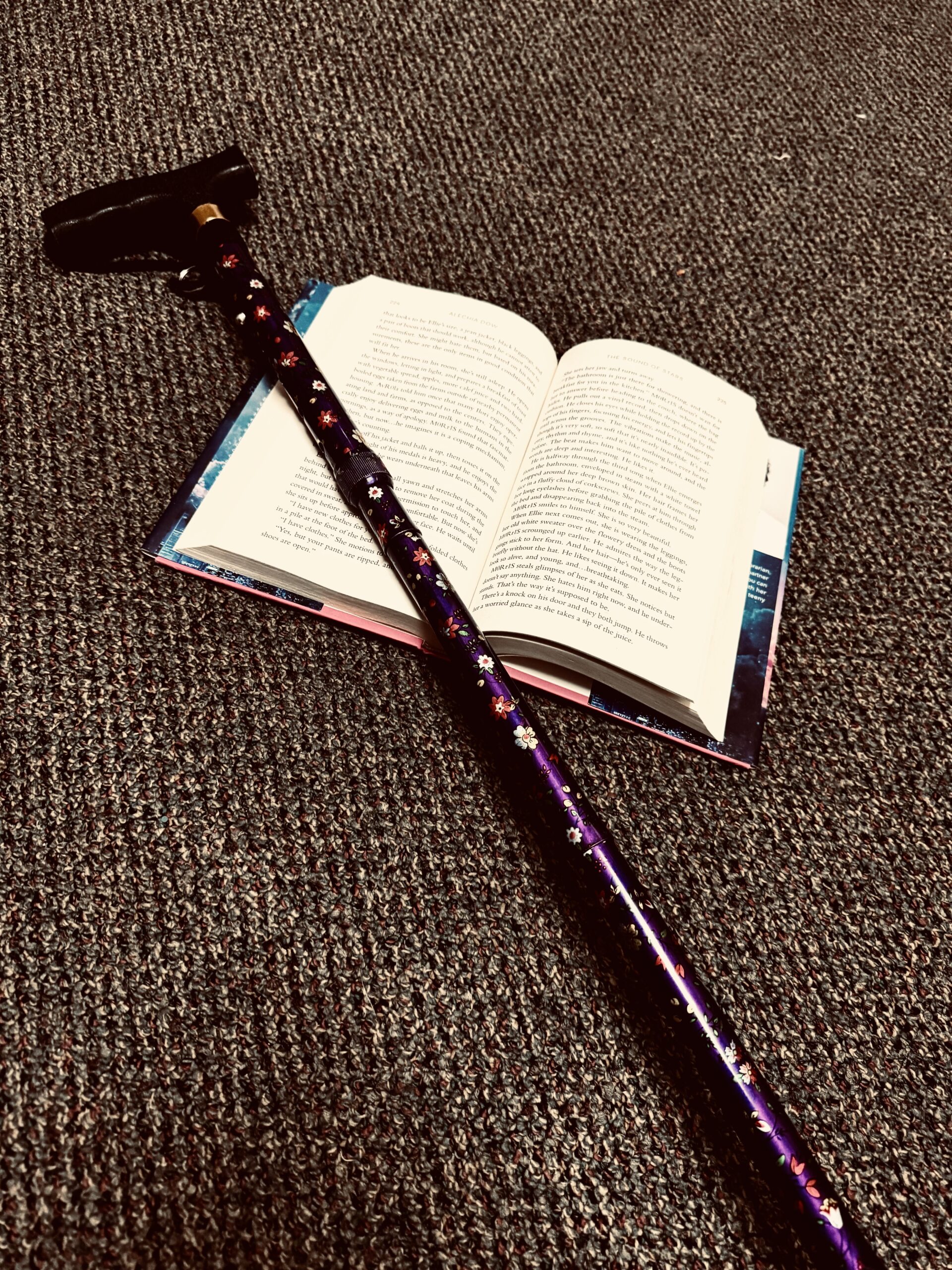

Disability Representation Across Literature: What Can You Do?

I have very weak hands, and I mean that quite literally. For one, I didn’t learn how to tie my shoes until the ripe age of twelve. Even as a college student, I’m dropping things left and right and frantically trying to cool off my fingers when they swell from holding...

Short Stories: The Bane of the Novelist

If you’re a long-form writer like myself, you know the struggle of reigning in your desire to provide every detail of your character’s life, or else risk your work becoming a massive info dump. You may also suspect that trying to start your career as a novelist with...

Superheroes: the Patron Saints of Infinite Suffering

Batman lost his parents at gunpoint at age nine. At the same age, I lost my mother to breast cancer. Ever since, feeling like half an orphan, I’ve always felt a special kinship with Batman and people that have felt the devastation of losing others. Since 2020, we all...

The Language of Flowers: How to Use Emotional Metaphor

“Yes, flowers have their language. Theirs is an oratory that speaks in perfumed silence, and there is tenderness, and passion, and even the light-heartedness of mirth, in the variegated beauty of their vocabulary. To the poetical mind, they are not mute to each other;...

Sculptors, and Painters, and Writers, Oh My!

For many writers, gaining experience and knowledge are major parts of the writing process. Barbara Kingsolver, the author of the creative nonfiction book Animal, Vegetable, Miracle spent a year focusing on eating locally in order to write a book about her experience....

Invitation to My Literary Dinner Party

Ever wondered what it might be like to meet a writer? To engage in conversation or to hear the perspectives from literary creators themselves? I present to you my literary dinner party with five writers sharing their insights over drinks, dinner, and conversation. ...

Creating Your Own Catalogue of Unabashed Gratitude: An Ode to Ross Gay

When I was young, I had a deep desire to prove I could be a great writer. At award celebrations in middle school, cool poets read these heartbreaking poems brimming with bruises, cigarettes and swearing. If my experience is at all normal, budding poets can feel...

On Your Mark, Get Set, Bake! Writing Exercises Based on the Great British Baking Show

The Great British Baking Show (also called The Great British Bake Off or GBBO) is a baking competition show that’s been on air since 2010. Unlike many other reality television shows, it relies on camaraderie between competitors and difficult baking challenges rather...

Laugh Your Way to Great Writing

When the world is burning, and the news seems to fuel that burn, I turn to comedians. Some might say this is naive and counterproductive, but I disagree (as long as Trevor Noah and Stephen Colbert are not your only news source). Humor is communal; laughter draws us...

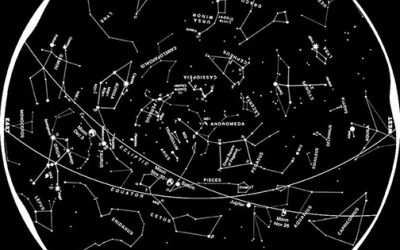

Writing Advice for Zodiac Signs

Now that we’re in Capricornus season, finishing at the end of January, it’s time to start bearing down on the project you’ve been dreaming about or pushing off. The changing of the seasons might find you seeking acceptance on creative avenues in your life. What’s...