Reviewed by K McCLENDON

If you are profoundly lucky, grief is something you know in name only. It has not yet made a home in the heart where someone you used to love once fit. Most of us carry on through the world ignoring death, attempting to make as little eye contact as possible. We assume tomorrow will come because if we didn’t, fear would make life impossible. But what happens when death becomes a force you can no longer ignore? What is there to do in life when you have no other option but to grieve?

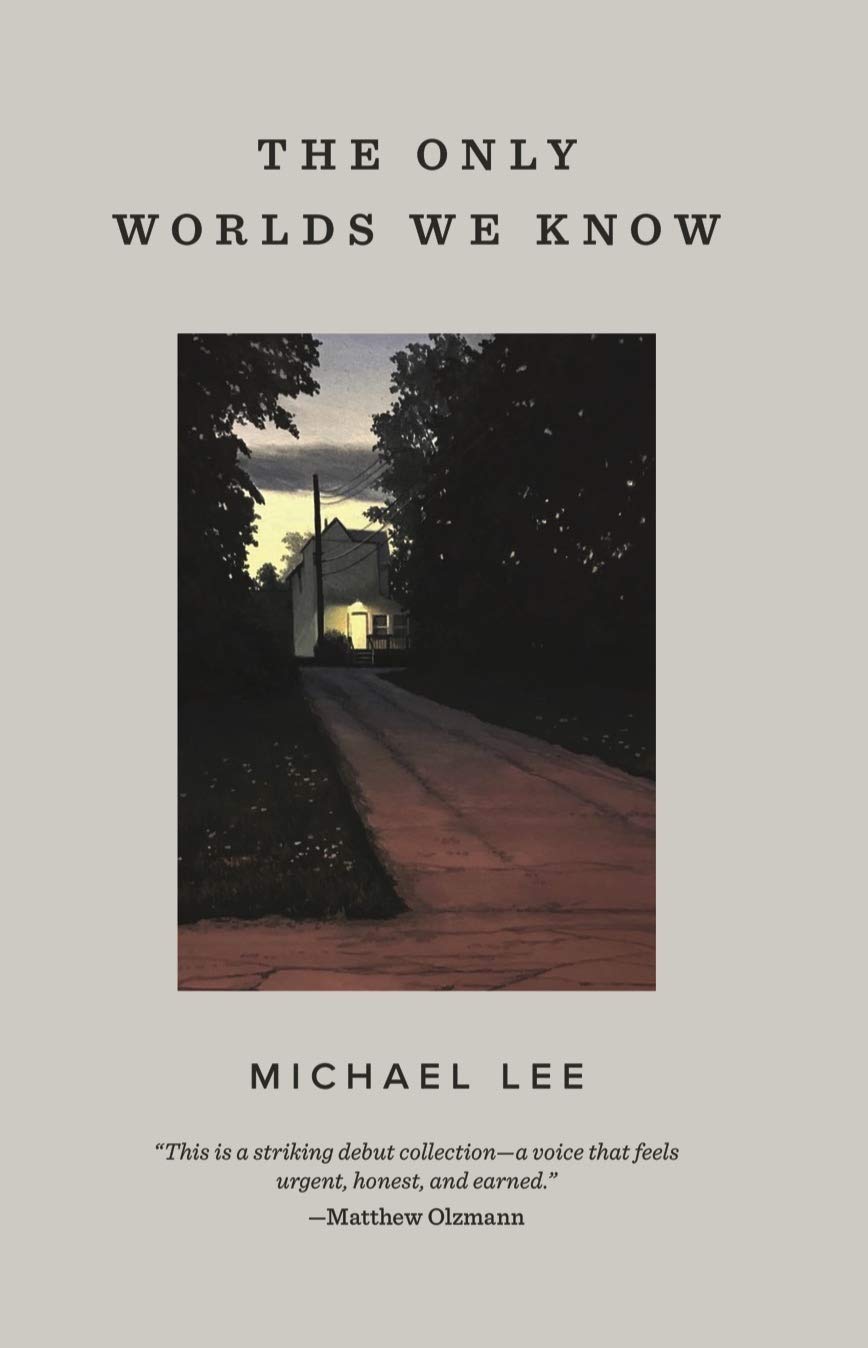

In his debut book The Only Worlds We Know, published by Button Poetry Publishing Fall 2019, Michael Lee teases out these impossible ideas of death. He navigates the loss of a beloved friend to knife violence and the thin line between life and death as a recovering drug addict.

There are many ways Lee attempts to describe death and its relationship to the body. A line from the poem “The Study Of The Dead And Puzzles” reads, “the knife does not kill the body it simply informs it / that death is possible; a single light flooding the room, / the one corner of the house we never knew / existed until all other rooms had darkened.” Another line from the poem “study of knives and music” says, “as if death is a kind of realization the body has.” Lee has an incredible way of giving death a soft side, a mystery that is not so terrifying. At the same time, he acknowledges that it is a sudden and incomprehensible thing the moment it happens. This balance is striking, as Lee is able to reduce death to a mere moment, the sun setting on a life.

Lee writes about the act of grieving. In “A group of dead friends is called a memory,” he places the reader now at a dinner table, imagining dining with ghosts. They sit in the loneliness that comes with losing loved ones to the unexpected horrors of life. There are enough plates for the living and but not for the ghosts to feast. Michael, wonderfully alive, tells stories of times when these ghosts were not yet undone. He attempts to reconcile his own living, by recounting joy.

When speaking of his life as a recovering addict, he emphasizes a different way of grappling with death. In the poem “Out There,” he writes about what it means for him to go to Alcoholics Anonymous and what it means when people stop coming to the meetings. “Each week a new man enters / the room, each week another man doesn’t / come back. What magic, to walk through / a door and then appear again as ink / in the Sunday paper. He went back out,/ the sentence a sentence… /and you wonder / where all these men have gone but you don’t / you know./ You know there is no long winter out there / where we dig through dead pines / in search of the bottom.”

In this poem, Lee interrogates death as both addict and a witness to addiction’s power. It is a fact that if the addict drinks, smokes, or otherwise gives into the addiction, death is not only possible, but it is unavoidable. Lee centers himself in the middle of it, an addict who has seen his future over and over again in the ones who have gone out. Lee comes to terms with sobriety only after death is accepted as imminent. On the page this poem has power that is unprecedented, Lee’s performance of it is second to none, watch it here.

Lee speaks of death with a control that makes it seem like a manageable moment we all must inherit. He does not let us forget there is beauty and grace in this too. He masters grief in a way that allows space to be held for healing. This debut book of poems exhibits mastery of the abstract, working to uncover the darkness and confusion of the only worlds we know.

Meet the blogger:

K McCLENDON is a junior at Hamline University where they study creative writing. K competes nationally as a spoken word artist. They have been an avid Button Poetry fan for many years and are now an intern at the company.

K McCLENDON is a junior at Hamline University where they study creative writing. K competes nationally as a spoken word artist. They have been an avid Button Poetry fan for many years and are now an intern at the company.