I heard mere fragments of my friends watching Smile (2022) from two rooms away and I’ve been sleeping with the lights on since. I loathe being scared. Yet, despite closing my eyes for the monster reveal every time I see a terrifying movie, I can’t seem to stop writing about grieving character arcs and religious trauma allegories driven by sinister creatures. Horror stories pique my morbid curiosity and often make me laugh harder than rom-coms and cry harder than period pieces. In trying to understand my fascinating internal dichotomy, I dove headfirst into the horror genre and discovered what a unique storytelling tool it is. Though it still unsettles me, I’ve come to revere its powerful cultural influence.

Horror has always been much more than blood, guts, and creepy crawly stuff. Since its conception, it’s been experimental and expressive: birthing science fiction and gothic, mixing myth with lore in social commentaries, anchoring cultural shifts, serving as an apparatus to examine historical injustice and cultural flaws, and enabling catharsis by facing collective traumas we’re often overfamiliar with. Horror does these things so well because it is, fundamentally, about making the audience uncomfortable. “When you enter into horror, you’re entering into… your own fear, your own darkest spaces,” writer Carmen Maria Machado explains. “When horror fails, it’s because the writer or director isn’t drawing on those things. They’re just throwing blood wherever and seeing what sticks. But horror is an intimate, eerie, terrifying thing, and when it’s done well it can unmake you.” Horror writers have to meet the heightened standards of a wary audience. The horror that haunts me with symbolism and abreaction does more than meet those standards; it exceeds them. However, in the mainstream, horror has always been critically and academically undermined. This was only exacerbated by decades of perversion horror faced on the page and screen. Fortunately, that distorted status quo is steadily being remedied thanks to the horror renaissance.

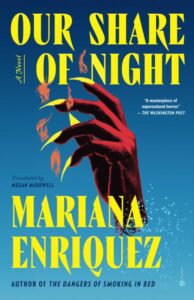

Literary horror is coming back better: as a tool, not just for the therapeutic effect and entertainment of getting the shit scared out of you, but for examining society’s shortcomings and personal trauma with an artistic lens that reframes these things for deeper and further exploration and understanding (a concept dubbed ‘horror vérité’). Crucial to the genre’s renaissance, horror vérité has developed in tandem with what Erika T. Wurth called the “egalitarian” community of authors engaging with horror. Authors who are queer, BIPOC, women, assault survivors, authors with PTSD, and in particular authors from Latin America are writing frightening stories with deeply personal and political messages rooted firmly in their horrifying lived reality. These diverse writers from marginalized communities are here, not to imitate the slasher formula, but to elevate the genre and step back into its psychological roots. On this revamped understanding of how compelling horror is, Machado paraphrased Mariana Enríquez, prolific Latin American horror writer and author of novels Things We Lost in the Fire and Our Share of Night, who said, “In real life… you don’t have the space to have the intensity of feeling that we should have when something horrifying or traumatic happens… [Horror creates] space for the person reading to have the actual emotional response that is appropriate to the thing that just happened.”

Literary horror is coming back better: as a tool, not just for the therapeutic effect and entertainment of getting the shit scared out of you, but for examining society’s shortcomings and personal trauma with an artistic lens that reframes these things for deeper and further exploration and understanding (a concept dubbed ‘horror vérité’). Crucial to the genre’s renaissance, horror vérité has developed in tandem with what Erika T. Wurth called the “egalitarian” community of authors engaging with horror. Authors who are queer, BIPOC, women, assault survivors, authors with PTSD, and in particular authors from Latin America are writing frightening stories with deeply personal and political messages rooted firmly in their horrifying lived reality. These diverse writers from marginalized communities are here, not to imitate the slasher formula, but to elevate the genre and step back into its psychological roots. On this revamped understanding of how compelling horror is, Machado paraphrased Mariana Enríquez, prolific Latin American horror writer and author of novels Things We Lost in the Fire and Our Share of Night, who said, “In real life… you don’t have the space to have the intensity of feeling that we should have when something horrifying or traumatic happens… [Horror creates] space for the person reading to have the actual emotional response that is appropriate to the thing that just happened.”

I wanted to understand why I felt drawn to horror, allured by the depth it seemed to reach into my mind, even though I still turned away if an unskippable ad for the latest demon-possessed doll movie came on. What I learned is that, ‘fraidy cat or not, I had been sensing the seeds of an influential and captivating genre about to bloom: the unique conventions of re-sensitization, catharsis, and horror vérité utilized by a new wave of insightful writers who have remade horror into a novelty in literature once again. I have always felt innately—and now understand practically—the cornucopia of sincerely profound possibilities that horror creates through the very fear that plagues me. In the moving words of Wurth, “Fear is powerful. If you can understand your fear, even use it to heal through the art you consume or produce—you’re so much further ahead than those who avoid it. Even if you’ll never completely understand it.”

Meet the blogger:

DARBI RENAUD is a student of Hamline University pursuing a BFA in creative writing. She hopes to obtain an MFA in the future. When she’s not writing, she’s usually sleeping with her cat sprawled out on or near her face.

DARBI RENAUD is a student of Hamline University pursuing a BFA in creative writing. She hopes to obtain an MFA in the future. When she’s not writing, she’s usually sleeping with her cat sprawled out on or near her face.