Blackout, erasure, found, collage—these are all forms of poetry that find themselves through use of pre-written words. (For this post, I’ll use “found” as an umbrella term). While sometimes diminished as lesser literary forms—either due to their simplicity or to the oversaturation of underdeveloped, fake-deep snippets on social media (who can forget “sbeve”)—found word poetry is perfect for shy beginners and experienced authors alike. With the styles’ flexibility and inherent interconnection, found forms can prompt and challenge through restriction, add to cultural conversations through the selection of source material, and empower writers to be vulnerable.

From the very beginning of the creative process, found forms subvert writers’ block. Existent works fill intimidating blank pages, and limited vocabulary inspires a focus on theme. Once your brain adds the lens of found poetry to its toolbox, inspiration is everywhere! I am often inspired by words and phrases gathered from overheard conversations, flyers, articles, etc. I collect these snippets in my notes app for inspiration and future use.

One might also seek out inspiration more actively. In a writing class I took through local gem, The Loft Literary Center, the teaching artist directed us to browse magazines or web articles in search of odd and interesting headlines. By erasing one word at a time, we created evolving stories through increasingly sparse reinterpretations.

Caption: Note the crediting of the publication in the title. Even though I took a critical stance on the headline itself, I still need to acknowledge its origin.*

This method is perfect for warm ups or writer’s block. Simply flip through a magazine, scroll through your collection of quotes or new words, or keep your eyes peeled for potential inspiration as you go about your day.

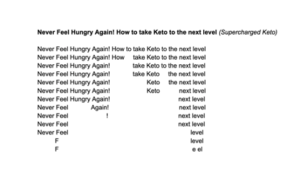

You don’t have to just stumble into inspiration for these forms though. You might be looking to respond to a certain piece or to add your voice to an existing dialogue. You may select a piece whose themes compliment your own, or a piece you wish to engage with critically. In the example above (“Never Feel Hungry Again!”) I use erasure and repetition to criticize the unhealthy implications of the selected headline, such as the idea that hunger, a natural bodily process/signal, is the enemy. By repetition, the reader is led to turn the phrase over in their mind. With erasure, I cut filler words and use empty space to intensify focus on the words that remain. Together, the repeating and slowly deteriorating lines create a monotonous cycle of depletion, representing the possible effects of following ‘health’ fads that attempt to reduce the body instead of nourishing it. When “erased” words are still readable, whether lightly crossed out or removed gradually (as seen above), you as a writer are able to walk readers through your critical process such that they come upon your intended conclusion organically.

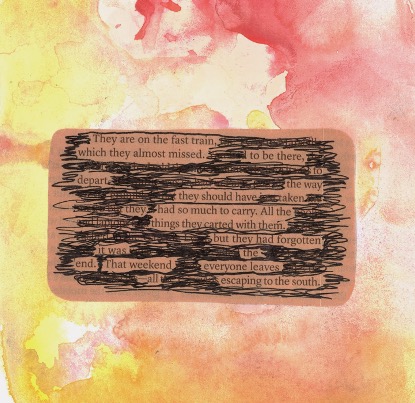

Finally, perhaps you want to share something personal, but writing out what happened in your own words feels too raw. Expressing your feelings through another’s words can provide a sense of protection. You didn’t need to say it; the words were already there. This emotional distance from the audience—or even from your own thoughts!—can be a powerful tool when starting to write about trauma and painful memories. You can have a voice without having to speak a word yourself.

You may have heard the idea that no art is truly original; I say, embrace it! Openly seek inspiration from the world and words around you! And next time you’re afraid to speak, or ready to engage, or just plain stuck, consider trying someone else’s words on for size.

*Important! A Note On Plagiarism: While this piece assumes good ethical practice on the part of the writer, it is important to respect the work of fellow writers by giving credit to the source of the words you use. As noted in an article on blackout & erasure forms in Writer’s Digest, your work should also be distinguished from plagiarism by being transformative. “There is a line to be drawn between erasure/blackout poems and plagiarism. If you’re not erasing more than 50% of the text, then I’d argue you’re not making enough critical decisions to create a new piece of art.” Remember, admitting to taking inspiration from the world and art around you does not make you less of an artist; in fact, giving credit to these sources builds your artistic credibility!

Meet the blogger: Maxwell Lakso (or just Max, to those who know him) is a junior undergraduate at Hamline University with a major in Psychology and minor in Creative Writing. He has a soft spot for unique (and concise!) forms, clarity balanced with eloquence, and joy as rebellion. Maxwell writes poetry and creative nonfiction, and plans to someday put out a chapbook. He enjoys collecting strange and delightful words in an ever-expanding list in his notes app.

Maxwell Lakso (or just Max, to those who know him) is a junior undergraduate at Hamline University with a major in Psychology and minor in Creative Writing. He has a soft spot for unique (and concise!) forms, clarity balanced with eloquence, and joy as rebellion. Maxwell writes poetry and creative nonfiction, and plans to someday put out a chapbook. He enjoys collecting strange and delightful words in an ever-expanding list in his notes app.