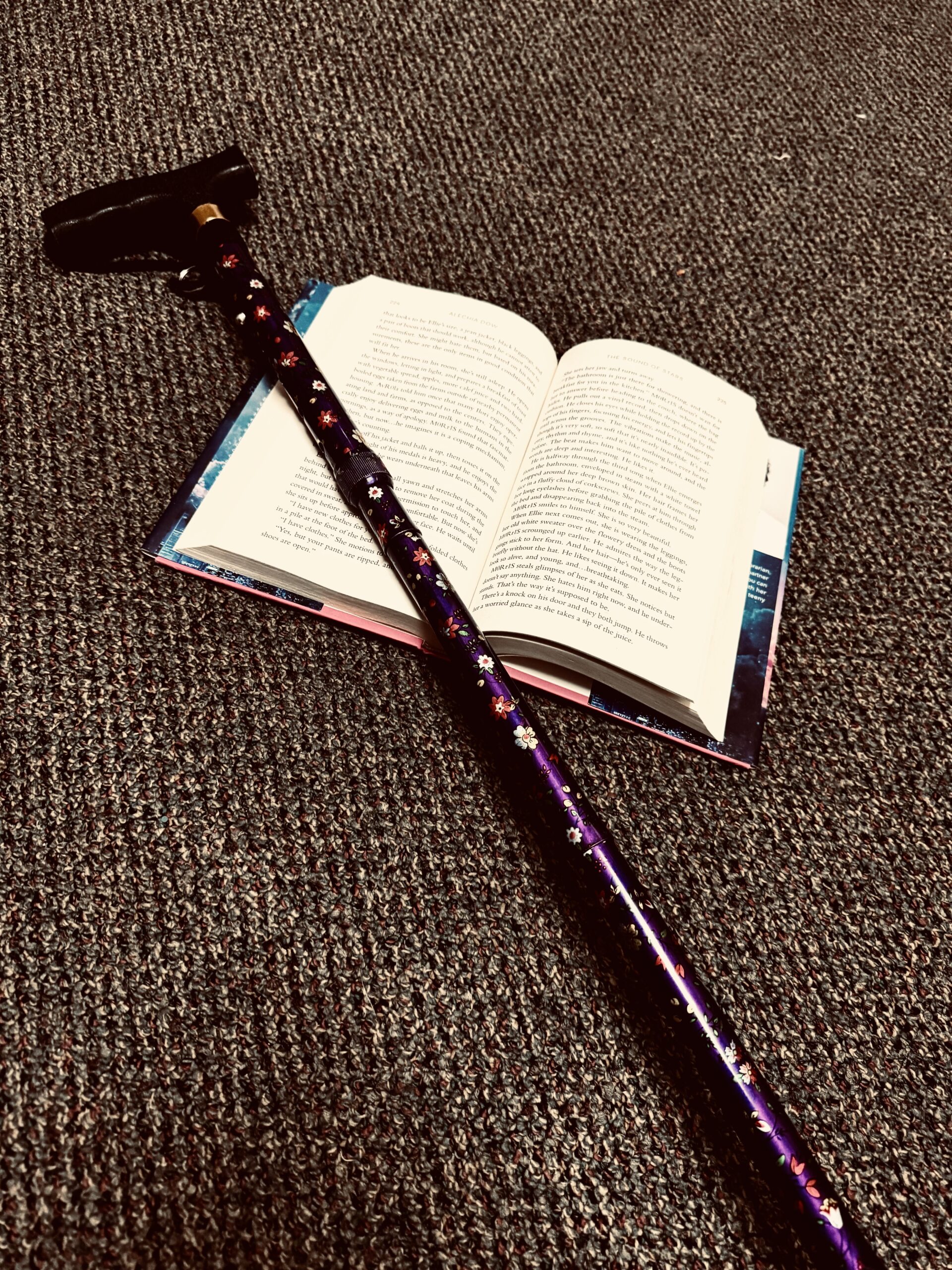

I have very weak hands, and I mean that quite literally. For one, I didn’t learn how to tie my shoes until the ripe age of twelve. Even as a college student, I’m dropping things left and right and frantically trying to cool off my fingers when they swell from holding plates and books. Opening bottles is a whole other adventure in itself. It’s safe to say I am envious of people who have functional, strong fingers. It’s uber-safe to say when I read a book series featuring a character with a paralyzed left hand, I emphasized hard with him. This character was Alex Stowe from the middle-grade series The Unwanteds, written by Lisa McMann, which I was (and still am) very much into. It was so cool to see a character that also struggled with opening doors and buttoning buttons. I was in heaven.

And then he dies.

He dies quite terribly, frantically trying to defend himself from an enemy with his other, non-dominant arm in the second saga of books. The characters mourn him and his role in the story is ultimately given to his abled younger sister. Life goes on.

Disability representation in literature has long been mixed. Rachel Petri, a disabled student contributor of Clearwater Press, once summarized that stories featuring disabled characters should strive to be real and hopeful and honest and encouraging. Petri brought up the differences between the book Wonder and the book Me Before You. Me Before You featured a story where Will, a disabled character, did not aspire to keep living, and as Petri describes, sent a message that living with a disability is not a life worth living. Wonder featured a story in which young Auggie, a boy with a facial deformity, realistically faced ups and downs, finding a support network.

Before Alex Stowe died, he struggled with implied PTSD and depression. He had nightmares for years about the woman who ultimately killed him. He drove himself away from his family and friends, becoming a shell of his former creative personality. One has to consider what message it sends to kill off a disabled character, especially one struggling with mental health.

Ultimately, The Unwanteds still holds an important place in my heart. I love the world, characters, and story and appreciate that the author was willing to take responsibility for potentially causing harm to her disabled readers. Over the past few years, I have gotten the opportunity to know McMann through a Saint Paul signing and a fun Italian dinner in Arizona; I consider her a dear friend of mine. I have begun to see myself in Lada, a disabled character with cerebral palsy from McMann’s newest series, The Forgotten Five. When writing Lada, McMann found a sensitivity reader in Stacy McNeely, a friend of McMann’s who has cerebral palsy. Lada is fun, intelligent, relatable, and showcases how variable disability can be. Sometimes she needs her wheelchair, sometimes she doesn’t.

So, what can we, as readers and writers, learn from characters like Alex Stowe from The Unwanteds and Will from Me Before You? Fay Onyx, a disabled contributor to the publication Mythcreants, has written quite a few articles on the topic of disability representation. In one of Onyx’s articles, the author discusses the ideas of challenging ableist language, researching harmful tropes (such as the villainous disability or inspiration porn tropes), and even suggests hiring a disability consultant. Another disabled contributor of the blog Metaphors and Moonlight shares similar thoughts. The author, identified as Kit, brings up how important it is to consider one’s reasons for bringing a disabled character into the story and to put research into portraying a disability accurately. Kit ends their post stressing how essential it is to go beyond fictional works and listen to disabled people in real life.

When writing a disabled character, remember that whatever you’re writing can greatly influence your audience and readers. Representation doesn’t have to be perfect but should reflect thoughtful research. The world around us is filled with accessibility barriers and harmful stereotypes, which are important to deconstruct when writing a disabled character. When in doubt, ask yourself if the representation you’ve written reflects careful consideration of disability, and how disability impacts the character in the story.

Meet the blogger:

ABBIE SUNDICH is a senior and aspiring author majoring in English and Communications with an Editing, Publishing, and Writing Concentration who will graduate in the spring of 2024 from Hamline University. Abbie enjoys reading, writing, drawing, photography, napping, and watching Netflix. She hopes to find a job with a publishing house or a nonprofit after she graduates, and specifically wants to write a few animal fantasy novels.

ABBIE SUNDICH is a senior and aspiring author majoring in English and Communications with an Editing, Publishing, and Writing Concentration who will graduate in the spring of 2024 from Hamline University. Abbie enjoys reading, writing, drawing, photography, napping, and watching Netflix. She hopes to find a job with a publishing house or a nonprofit after she graduates, and specifically wants to write a few animal fantasy novels.