REVIEW:

REVIEW:

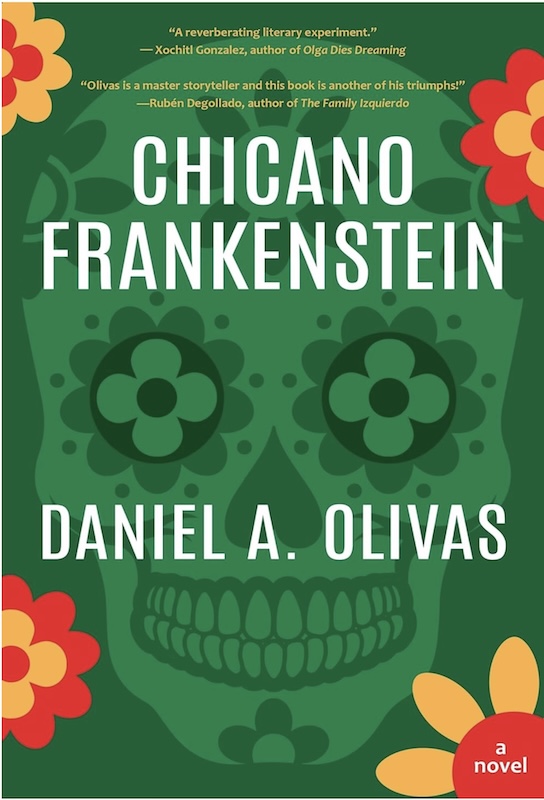

Chicano Frankenstein

Runestone, volume 11

“REVIEW:

Chicano Frankenstein

Runestone, volume 11

Reviewed by Jamal Awil

—

The Shelleyan progeny is tenacious. It has been transmuted from creator to creature, brute to brute maker, and evil to Ekron himself. In antebellum America, Conservatives used the Frankenstein metaphor to shun the rebellion of the enslaved people by the perceived threat of slaveholders, arguing that freedom would lead to chaos and destruction. However, abolitionist writers, particularly African Americans, reclaimed the Frankenstein metaphor to expose the horrors of slavery and its perpetrators, challenging racist ideologies. They inverted the metaphor from the enslaved people to the enslavers’ monstrosity, highlighting the dreadfulness of the enslaver and the system of slavery. Beyond individual characters, the Frankenstein metaphor was used to remark on the American nation. Its creation through a violent revolution against its parent nation, Britain, mirrored the monster’s rebellion against its creator. Mary Shelley‘s personal views, revisions to the novel, and the diverse interpretations the novel elicited throughout history all contribute to this multi-layered meaning. Mary Shelley’s “hideous progeny” has thrived and “prospered” as its architect predicted.

In an era when we are no strangers to political and social change, reading Daniel A. Olivas’s Chicano Frankenstein can ease anxiety. Published by independent Forest Avenue Press, Chicano Frankenstein is not just a reinterpretation of Mary Shelley’s classic but a powerful critique of the US social and political order that condones harassment and exclusion. Olivas’s novel is set in a near-future world wrestling with the moral complexities of reanimating the dead to feed the shrinking and lustful capitalist workforce.

The narrative circles around an unnamed paralegal brought back to life with the memory robbed from him. As the novel calls him, the Man navigates a world that relies on and rebukes the reanimated, referred to as “stitchers.” This alienation, so clearly highlighted by President Cadwallader’s tainted rhetoric, echoes the creature’s outcry in Shelley’s original: “I am malicious because I am miserable. Am I not shunned and hated by all mankind?”. This juxtaposition underscores the enduring human struggle for acceptance and belonging, which resonates deeply with readers.

Complicating the Man’s identity is the mismatch of his reanimated body parts, making him feel like he “didn’t belong anywhere. Neither here nor there.” This manifestation and frustration mirrors his internal struggle to reconcile his present reality with the absence of personal history. “How can you have a future without a past?” Faustina, his Date, poignantly asks, kindling the existential dilemma at the core of the Man’s quest. This profound exploration of identity and belonging will leave you feeling introspective and contemplative.

His quest for his origins takes him to Dr. Prietto, who reanimated him. Dr. Prietto, on his part, wrestling with his ethical complexities, discloses he had planted a clue, a children’s book, among the Man’s belongings. “A falta de pan, tortillas,” which translates as “In lack of bread, there are tortillas,” the doctor explains, characterizing his attempt to offer some semblance of identity to those he reanimated.

The novel folds a loop with love and the power of the human condition. The man’s lack of history challenges his relationship with Faustina. “They’re kind of a clean slate,” a character in the novel observes, echoing the dilemma of loving someone stripped of their past.

Olivas intersperses Man’s journey with a satirical critique of contemporary political discourse in a masterful narrative that echoes John Steinberg. One unique narrative that one never finds commonly is Olivas’s use of news reports, political ads, and Oval Office transcripts to expose the duplicity and fear mongering surrounding the reanimated community. “God didn’t make them; science did. They’re not really like us, are they? They’re not my kind. Are they your kind?” Secretary Miller’s scathing words during a televised interview expose the insidious nature of prejudice and othering.

Chicano Frankenstein is consistent with Olivas’s dystopian, critical, and introspective genres. It is a provocative quest for identity, belonging, and the human condition. It challenges readers to confront their biases and contemplate scientific advancements’ ethical implications. Olivas’s novel is a timely reminder that the monsters we fear are often reflections of our prejudices and insecurities.

JAMAL AWIL

Hamline University

Jamal Awil is a literary enthusiast who loves reading literature without discrimination. He is now a member of the Runestone editorial committee on the upcoming issue and an undergraduate student at Hamline University. Passionate about words and their power, he runs a new literary journal, Polymath Review, from his basement.