Community is Everything:

An Interview with Chavonn Williams Shen

The following interview with Chavonn Williams Shen was conducted in-person by editorial board member Alexander Bailey in a small lecture hall in front of the Runestone editorial board and community members. This interview was transcribed and edited for clarity by faculty editor Halee Kirkwood and board members Elena Laskowski and Korissa Lange.

CHAVONN WILLIAMS SHEN (she/they) is from Minneapolis, Minnesota. She was a 2022 McKnight Writing fellow and a first runner-up for The Los Angeles Review Flash Fiction Contest. She was also a Best of the Net Award finalist, a Pushcart Prize nominee, a winner of the Loft Literary Center’s Mentor Series, a fellow with the Givens Foundation for African American Literature, and an instructor for the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop. A Bread Loaf, Tin House, VONA, and Hurston/Wright workshop alum, her writing has appeared in: Diode, Anomaly, AGNI, and others. Her debut book, Still Life with Rope and River, (Finishing Line Press) came out in the fall of 2024.

ALEXANDER BAILEY sits as an editor at Runestone, Hamline University’s premier literary journal. They enjoy writing fiction and examining systematic issues within the arts. They are currently pursuing degrees in theatre arts and English at Hamline University, and are slated to graduate in 2026.

Alex Bailey: What a joy it is to be able to hear you speak the poems. I think a lot of us can agree in this room that poetry is meant to be heard by the poet, and that’s what makes it so special. So thank you for being here. Many of the poems in your book hold space for the murder of Emmett Till. To you, what is the importance of history and poetry, both together and separately, and history through poetry?

Chavonn Williams Shen: I think about that old quote, “those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it.” And I add to it, those who know history are doomed to repeat it. I feel like history is so cyclical, it’s kind of hard to avoid. And I feel like that in my poems, how there are echoes of Emmett Till, but I also talk about Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, how these deaths weren’t that long ago, and how Black death has a cyclical manner historically and currently.

The role of history in poetry? Well, at least in my poetry I feel like history is kind of the through line, I write from the place of history. I think about the stories that my dad has told me. A lot of them have ended up in this book, and they become poetry in themselves. So, history is a form of poetry and a way to further emphasize my poetry.

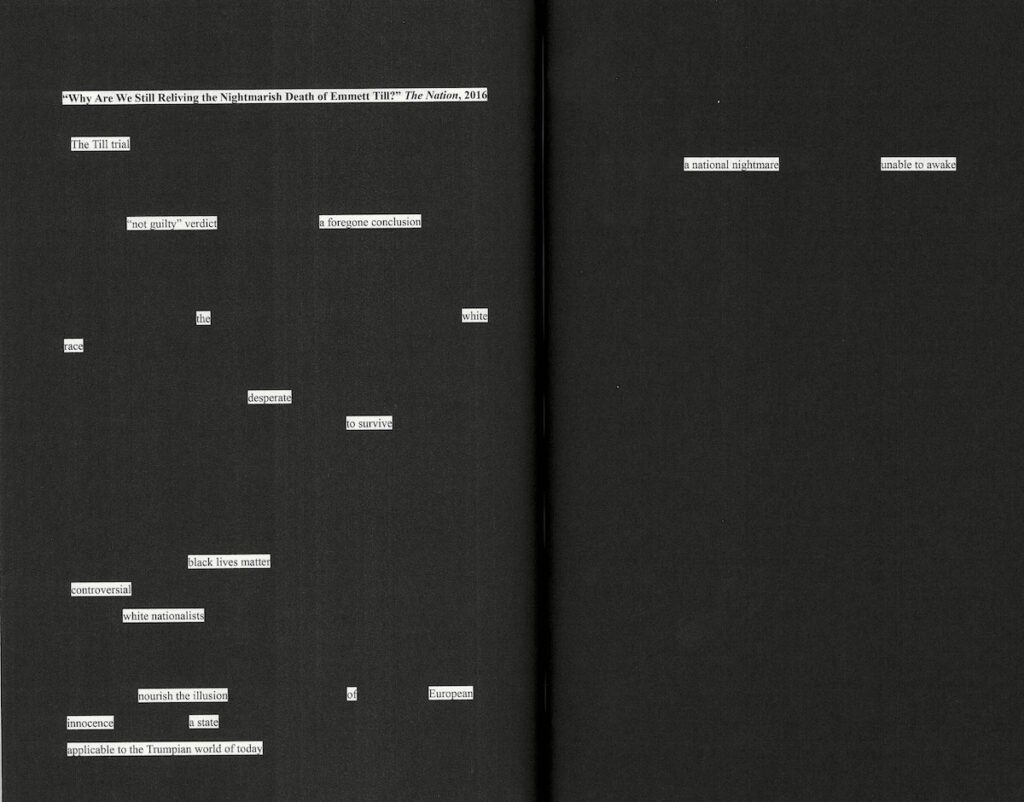

AB: In that kind of same vein, alluding to where your grandfather grew up in Pike County, how does ancestry influence form? In particular, I think about the poems in this book that reference your grandfather’s house or the road to your grandfather’s house. There are also poems that are blackout poems from newspaper articles. So how does ancestry influence form in that way?

CWS: I think it goes back to what I was saying, that history is a through line in my poetry. Ancestry is so common in my poems that it just becomes another poetic device, like rhythm and imagery. Ancestry is another thing that I pull from my poetic toolkit.

AB: In that kind of same vein, alluding to where your grandfather grew up in Pike County, how does ancestry influence form? In particular, I think about the poems in this book that reference your grandfather’s house or the road to your grandfather’s house. There are also poems that are blackout poems from newspaper articles. So how does ancestry influence form in that way?

CWS: I think it goes back to what I was saying, that history is a through line in my poetry. Ancestry is so common in my poems that it just becomes another poetic device, like rhythm and imagery. Ancestry is another thing that I pull from my poetic toolkit.

AB: I think that [ancestry] is something that a lot of us can explore, something that I don’t know a lot of us do explore. And so it’s really interesting to see somebody explore their ancestry in that way.

In your poem “Interview with Carolyn Bryant on the Anniversary of Emmett’s Death, how and why do the poems that include redactions encourage or discourage censorship, and the ability for the reader to forget because they cannot see?

CWS: That’s a really good question, and a difficult poem! I was wondering if anybody was going to ask about that one. I figured somebody was going to ask eventually and it’s time for me to be brave. There are a lot of poems in this book that scare me. Not just because I wrote from a place of fear, but just presenting them to the world is scary. I know that in order to be a writer, I have to do things that are scary. Publishing this book is just one of the ways to prove to myself that I can do hard things.

I feel like redacted texts are a way to implicate the reader in ways that fully visible texts don’t, because your brain is forced to fill in the blanks. I think about the poem “Press Release”, when I write “we regretfully inform you, (Black person’s name) was shot while (existing/saying don’t shoot).”

There’s a way that the reader is forced to be a part of the poem by imagining things, filling in what those blanks might be. The poem “Interview with Carolyn Bryant” is a made-up interview, but there’s so much that wasn’t said as seen through the blackouts and I really wonder what people think was said within that.

AB: Many of us are aspiring poets and authors in the room. What advice would you give to them, whether it be how to explore their own ancestry or how to gather the courage to write? What would you offer to the people in this room?

CWS: When I was an intern for Coffee House Press, a publishing company that is based in northeast Minneapolis, the head editor at the time, Chris Fischbach, had told me that good writers are even better readers. So, read constantly. I know some writers who write without reading, and I think it’s a form of hubris, to not do the work of reading. Read constantly, read whatever genres you can get your hands on. If you write in poetry, read in fiction, and vice versa for whatever genre you’re in. Read widely.

AB: Do you have any specific recommendations that you’re reading currently?

CWS: I’ve been reading a lot of manga. I just finished the super queer manga, Bloom Into You. Has anybody seen it? It’s really, really good. I think it is a fun way to stretch my imagination. It’s one thing for me as a poet to read poetry, but what about graphic novels and an extension of that, manga, reading things in a language that is not mine.

Oh, something else that I’ve been reading is Watchmen by Alan Moore, which is also a graphic novel, a classic. I highly recommend it.

AB: Well thank you, Chavonn. We’re going to turn to questions from the audience now!

Audience member: What’s happening [to Black people] today is a reflection of what happened to [Emmett Till]. Now we have social media to tell a different narrative. How has social media affected how people in this country make assumptions about the current political reality of Black people today?

CWS: Can I answer with a poem? There’s a poem that answers, I think, that question from page 42.

So I think, especially in the current political climate, how is this not relevant?

Audience member: I noticed that in the book you had multiple poems titled “Legion”, and I was curious why they’re all titled the same.

CWS: So the story of “Legion” is based off this Bible verse in Mark. There was this girl who was possessed by demons, and Jesus came to cast out the demons and he had asked what the demons’ names were and they said ‘“Legion”. Rather than having a singular name, they’re this great, vast army, and then instead of Jesus sending them away, the demons asked to be put into pigs. And then Jesus did, and the pigs ran off a cliff and died.

And apparently the Legion story is supposed to be an analogy for the Roman army and how military might can only go so far before justice can be served. But…the wider analogy didn’t come to me as much as the term legion, having a singular voice for many things, for many people. I thought a lot about Greek tragedies and how they have a chorus. In the Greek tragedy of Medea, there’s a narrating chorus that’s kind of how the Legion functions. A chorus of Black people who’ve died by violent means become the narrators throughout the book.

Audience Member: How do you keep telling your stories and your emotional truth when the majority of people aren’t encouraging it or are dismissing it?

CWS: I really like that question. I think my book is an exploration of what is the truth, and whose truth is the truth. You have Carolyn Bryant speaking her version of the truth, which felt true to her. Contrast this with Emmett’s great uncle, Moses Wright, whose truth felt true to him. And then Emmett himself, having a form of truth.You have all these competing truths. It becomes one tangled knot, and my job as a poet is to pull out the strings to try to get to the center of that truth.

I also think my job as a poet is to explore that knot and not always try to unravel it. Emotional truth can exist in multiple forms. So it’s not necessarily myself dismissing different perspectives, but rather looking at the competing emotional truths and trying to see what I can glean from it within my own writing.

Audience member: How long did it take to get your work published?

CWS: So I started writing the book [Still Life with Rope and River] in 2018–actually in Richard Pelster-Weibe’s class at Hamline. I finished it in 2023, and then I started sending it out. It took like three months. That’s really uncommon though. And there were a lot of rejections in it.

Audience member: In the process of publishing this book, how important was it to you to find a publisher that aligned with the message you’re trying to convey?

CWS: Ooh, that’s a really good question. There were definitely some publishers that I passed up because I didn’t think they were in line with my vision, but ultimately I just wanted a publisher who I knew would support me. I think that’s all you can ask for in a publisher, just somebody who is willing to take a chance on your work.

Audience member: I was wondering if you could speak a little bit more to what it’s been like to publish this first book. What’s been scary about it? And also, what’s been joyful about it? Where have you found something new?

CWS: I can start with the joy part, I think I need more joy in my life. I think it’s been really amazing to see how my community has come out to support me in so many ways. Like my bestie Hillary here, who would be the bookseller, and Halee, making my book and making it a part of your curriculum. That’s so fricking cool. I feel so greatly supported by the people around me, and it’s been cool to have my book manifest that support.

As far as challenges or things that are scary, I think just putting your work out into the world and having somebody judge it is scary. And I’m sure you guys all know in a class that has to do with submissions, that people are putting some of their really personal stuff out there, and you guys are reading them and deciding “oh, this doesn’t fit, this fits, this doesn’t fit.”

And it may seem like an arbitrary process to outsiders, but I know that there’s a lot of intention that goes into how you create your issues. And I say the same thing with publishers and presses. It may seem like an arbitrary process to the outside, but I know that there’s a lot of intention within it. However, that doesn’t make it less scary to put your work out there.

Audience member: What was your experience editing this book? Was there a magic number on how many revisions it took before you finally got it right?

CWS: There is no magic number, sorry to disappoint! As far as the editing process, somebody had asked a similar question at my book release this past Thursday, about my editing, and I guess I edited until I felt like stopping. I know that’s a very unsatisfying answer, but it’s the truest answer. I wrote until I felt like I couldn’t write anymore.

If the poem is a house, then when I feel like the door is jammed, when I can’t open the door anymore, that’s how I feel like the poem is done. When I try to be as expansive with the form, as expansive with the content as I can, and then I did all this editing, and then I run into this wall, this closed door, and that’s how I know that I’m done editing.

Audience Member: When your editors give you feedback for changes, how do you go about deciding which edits to accept and reject?

CWS: I try to be open to all kinds of feedback, to find a kernel of truth even in something I disagree with. Even if it can be the most heinous of feedback, maybe there is something that I can learn from it. If nothing else, I know that this person doesn’t understand my writing the way that I want them to. And that’s the kernel of truth that I can take away.

Audience member: Did you change up the order of the poems in the editing process?

CWS: I am a child of the 90s and early 2000’s, and I think about my books like mixtapes or playlists. I try to create a narrative arc within my mixtapes. How does one song lead into the next? What do I want the listener to feel? A mellow song can build up into an intense song, a song with a bunch of guitars then fades out. Whenever I am writing something, a manuscript of multiple poems, I always think, what narrative arc do I want to tell within my book? How do I want the reader to experience my book in order?

And that being said, the order that it currently is in is very different from the one that I had originally turned in to the editors. Because I was able to find a narrative arc that I thought fit the content more.

Audience Member: Could you talk about the process for the book cover? Did you have a vision in mind for what you wanted? Were you paired with an artist?

CWS: The artist is Royce Calevera, who had done my website and my business cards and some other stuff. The cover is actually a combination of poems—you see the tire swing from ‘Walthall County’, the shoe from ‘Pike County’, the magnolia trees from multiple poems, and the river poems like ‘Ode to the River As It Comes Undone’. So it’s a bunch of different elements in my poems that were able to be thrown together.

Halee Kirkwood (Runestone Editor): That’s kind of a rare cover story, because often what a small press will ask you to do is choose a free use art image or existing art that you can get for free. And so I think your story is really unique in that you literally commissioned someone to incorporate elements of your poems into an image.

CWS: One great thing about Finishing Line Press is that the process for choosing my cover was so freeing, they let me do whatever I wanted. Which of course can be daunting, but it’s also liberating. Finishing Line Press has a lot of really beautiful covers, and that’s because people commissioned them to be specific to their work.

Audience member: I really like how expansive your play with form is. I’m curious what inspires you to write specific poems’ content with the form?

CWS: Something that I think about is, why should all my poems be left aligned? There is an entire page, so I can fill up that page. Just play with the way that poems look. I love how the writers Douglas Kearney and Chaun Webster in particular do a lot with visual poetry and they inspire me to be even bolder in my work as far as how I place things on the page.

And something that I think about in poetry and writing in general is, how does the form suit the content? So, I try to use forms that I think would suit the content well, like how the poem about the noose is wide and expansive because it’s like the noose is looking down and it’s a wide scope. Or my poem about sobriety feels like it should take up the page because it’s taking up a lot of space within me. In contrast to the Legion poems, they feel way more constrained.

Audience member: You have a YouTube channel where you play guitar…

CWS: Oh my gosh, you found that? Oh my gosh, that’s so embarrassing…my Fall Out Boy covers from like the early 2000s, me playing guitar and singing. What about my covers?

Audience member: They’re really good.

CWS: Oh, well, thank you! Is there anything else you wanted to say about my YouTube?

Audience member: I always wonder how poetry and music are connected…I love performing poetry and I think it’s dying because I don’t usually see it around.

CWS: I wouldn’t say that it’s necessarily dying out as far as the performance aspect of poetry. Button Poetry is alive and well. They are the biggest distributor of spoken word in the world, I think. And they’re based in downtown Minneapolis. Look through Button’s work and they have tons of performance poetry, performers who are really in tune with their musicality. When I was in my MFA program, we often talked about page poets versus performance poets, and I consider myself way more of a page poet because there are little tricks that I do on the page that are hard to translate in spoken form. There are times where I’ve tried and that’s definitely a challenge for me, but it’s something that I need to explore more rather than something that I already have answers for.

But yeah, the songs that I wrote….that’s so embarrassing to think about!

Audience Member: No, it’s cool! It’s multimedia.

CWS: [Laughs] Multimedia, I’ll accept it.

Audience Member: You’ve been to a lot of residencies and workshops—the Tin House workshop, VONA (which is for writers of color), Hurston/Wright workshop; you’ve been a winner of the Loft Literary Center’s Mentor Series. What is the benefit of attending a workshop or residency? What do you look for when you apply to them?

CWS: When I looked for residencies and workshops, specifically when I was in my MFA program, I was looking for where I could fill in the gaps, where was there somebody who can teach me something that I can’t learn in my MFA program.

VONA, which stands for Voices of Our Nation Arts, was founded by Junot Díaz and Elmaz Abinader. VONA was founded for people of color, specifically founded to help people of color with their MFA trauma. And I definitely have plenty. So VONA, was a really great addition to my MFA in building community there. Patricia Smith was my VONA instructor, and she does a lot of persona poems. And there weren’t a bunch of people at Hamline who I knew exclusively worked in persona poems or worked extensively in persona poems. So that’s what drew me to working with Patricia Smith.

When it comes to applying, I say cast your nets widely, because you’re probably going to get a lot of ‘nos’, but the ‘yesses’ are still worth it. And even if you don’t get in one year, keep applying. I’ve applied to Cave Canem, which is a program for Black writers, and this is my third time applying. But I know that my application gets better and better the more I apply.

Audience Member: You have some really good publications (you’ve got the runner-up for the Los Angeles Review Flash Fiction Contest; AGNI, which is quite a prestigious journal), and so I was wondering if you could talk about your experience publishing with literary journals.

I guess it’s kind of like asking who your favorite child is, but what’s your favorite publication, and why?

CWS: I think my favorite public publication was my one for the Los Angeles Review. It was a flash fiction piece written from the point of view of Thomas Jefferson about Benjamin Banneker, who was a Black architect that helped design Washington, D.C., in the early 1800s/late 1700s. Thomas Jefferson had written to him like, ‘oh my gosh, you’re so amazing’. And then Benjamin Banneker wrote back like, ‘uh, you have slaves’. And then Thomas Jefferson wrote this really non-committal letter. It was just like the epitome of white fragility, before white fragility was a term.

In the piece, Thomas Jefferson is talking about Benjamin Banneker in ways that were really unsavory, but that also highlighted the experiences that I had in academia pursuing the sciences. I have a degree in psychology with an emphasis in neuroscience (and then I ended up getting my MFA in creative writing).

So, specifically this piece is about my experiences as a Black person–and the singular Black person in a lot of scientific spaces, and I guess a lot of academic spaces–and how Thomas Jefferson objectified Benjamin Branneker. Like ‘oh, you’re one of the good ones.’ If you check out any of my other writing, I recommend that piece.

In terms of my process of submitting to a literary journal, I know that people have actual standards, but I kind of do it very haphazardly. Well, at one point I did it haphazardly, but now I use Duotrope. You really get what you pay for when it comes to Duotrope, because they show the acceptance rate, how long it takes on average for somebody to be accepted vs. how long it takes on average for that person to be rejected. They show how many people who are currently members of Duotrope have submitted to that magazine, and their pending pieces. They also show a list of reasons for rejections.It’s helpful data, and has given me structure to my submission process.

Audience Member: I know you just had a book come out now, but are you working on anything at the moment that you’re excited about and able to share?

CWS: I’m working on a collection of love poems [excited gasps]. I feel like there aren’t a lot of modern love poems–or there are, but not in the ways that I describe them. So my book will be love for places, love for people, falling out of love—just trying to expand the definition of what love is and the way that people see love, rather than just romantic love or familial love.

HK: What advice do you have for writers and editors working in an uncertain time in history?

CWS: Read marginalized writers. Read BIPOC writers. Go support local bookstores. Cause we need the community and we need the support. We need all the community we can make and have in these times. Community is everything.